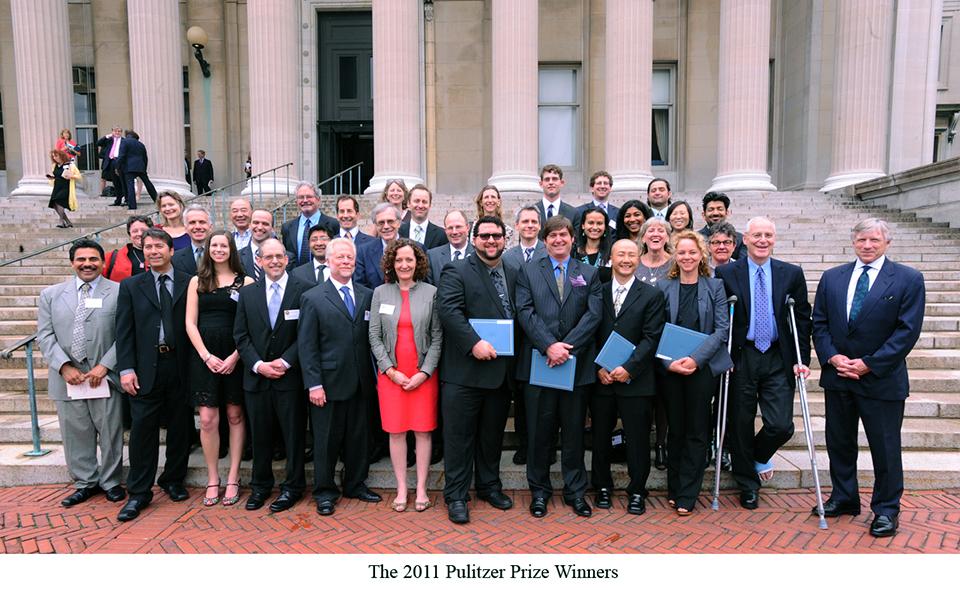

2011 Pulitzer Prize Luncheon

Co-chair of Pulitzer Prize Board

Kathleen Carroll's Remarks

What an incredible pleasure it is to be with all of you on this glorious day of celebration. And on behalf of the Pulitzer Prize Board, let me offer you the warmest congratulations on your achievements.

The Pulitzer Prize has been around a while _ the first ones were awarded in 1917 _ and a few traditions have grown up over the years.

One is this lovely luncheon under the Rotunda of the Low Memorial Library. Here, glasses clink, hugs are exchanged and everyone is enveloped in a warm fuzzy glow.

About that glow. You might go easy on the bubbly until after you have to navigate the steps to the stage and have your photo snapped with President Bollinger.

Those photos, you know, will live on the Pulitzer web site forever.

And once you’ve attained that hyphenated state, you’ll be asked to give back; participating in a Pulitzer seminar or perhaps serving on one of the hardworking juries that vet the hundreds of entries submitted each year for consideration.

The arts jurors work for the better part of the year, reading hundreds of books, listening to hours of music and watching dozens of new theater works.

They collaborate, sometimes vigorously but always collegially, to identify the three best works in each of the categories _ fiction, non-fiction, history, biography, poetry, drama and music.

The journalism jurors gather here at Columbia each spring for three very long days to pore over hundreds of journalism entries in local, national, international, explanatory, investigative and breaking news reporting, in feature writing, commentary, criticism, editorial writing, cartooning, feature photography, news photography and Public Service, the only prize that always goes to an entire news organization rather than individuals.

Those juries also put forward three finalists in each category.

That collection of finalists then goes to the Pulitzer board members who spend several months reading and contemplating the work until we get together in April to discuss and vote on the winners.

For each of us fortunate enough to serve on the board, those two days are a joy, filled with thoughtful and reflective discussion of amazing journalistic and artistic work.

Those Pulitzer categories are not static. They have changed many times over the years and they will undoubtedly evolve more in the years to come.

But whatever the category, the work always captures one thing ... the sloppy, elegant, tragic, heroic mess of human existence.

Looking back over 94 years of Pulitzers, you can see how news events move off the front page and into the hard covers of books. They seep into plays and poems as we struggle to make sense of the acts of nature and the actions of man.

Year after year, journalism prizes are awarded for the coverage of death. The earth heaves and hundreds of thousands die. Deep inside a young mother, cells go haywire and disease takes her. Young men die fighting over land, ideals or even insults.

From this news coverage, we learn.

Then artists come along and bring us a new understanding. Death becomes an excruciating examination of loss in a play like "Rabbit Hole," in the poems of "Late Wife" and in fiction like "The Road."

In the past decade, awards have gone to the riveting photographs of war; devastation in the battlefield and on the home front. We have read about the soldiers and the ordinary people upon whose land they fight and we learned about once-secret policies invoked to staunch acts of terror. Winning books like "Ghost Wars" and “The Looming Tower,” examine the seeds of those conflicts and writers and artists will surely continue that examination for years to come.

Our evolving and imperfect views about race also permeate the work.

Slavery and the Civil War predate the prize but over and over, we strive for greater understanding of them with new research or fresh views in histories like "The Dred Scott Case" and "A Nation Under Our Feet," or the fictional story of a black family that comes apart when one member takes slaves in “A Known World.”

And Wynton Marsalis, squeezing the sound of pain through his trumpet in “Blood on the Fields,” his oratorio on slavery, gives us yet another way to learn.

In the 1920s, newspapers repeatedly won the prize for exposing or standing up to the insidious Klan. Eight decades later, the non-fiction work "The Race Beat," would explore how newspapers did, and did not, cover the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Photographs from the era sear the images for us: James Meredith felled by shotgun blasts on a Mississippi road, back arched, his mouth howling in pain.

Journalists say they don’t like to repeat ideas but thankfully biographers and historians understand the need to examine events and people anew.

A biography of Andrew Jackson won the prize in 2009; so did one penned in 1938. Theodore Roosevelt was the subject of winning work in 1932 and 1980, his cousin FDR in 1949 and 1972.

Abraham Lincoln appears frequently, including this year, and may be central to winning work in the greatest number of categories; history, non-fiction and with the 1939 work “Abe Lincoln in Illinois,” in drama.

Those of us who work in non-fiction fields occasionally look with envy at the crafters of fiction, poetry, drama and music. We think “How lucky to be able to shape reality yourself...” knowing, of course, that creation is much harder when you don’t have all the characters and their actions handed to you.

The very best of those works can sometimes exposure reality more clearly than real life itself.

There is a scene in this year’s fiction winner, “A Visit from the Goon Squad,” in which two characters sitting at a table give up talking with each other and finish the conversation by typing at each other on their devices.

Anyone who has ever announced that dinner was ready by texting family members who are simply in another part of the house know that fictional scene is as real as it gets.

So let me close with one more small bit of advice: Enjoy this day.

Luxuriate in this celebration and savor all the people who are here, sharing it with you.

The work begins again soon enough, so for now, have a marvelous time.

And now, enjoy your lunch and as you wrap up dessert, Pulitzer Administrator Sig Gissler will be back to resume the rest of the program.

Thank you and good afternoon.

Co-Chair of Pulitzer Prize Board

Ann Marie Lipinski's Remarks

Some years ago, following the death of my beloved maternal grandmother, I spent an afternoon reading her diaries. This was no breach. For as long as I could remember, my grandmother’s diary lay open upon her dining room table, as accessible to a visitor as her daily newspaper. In it she recorded the brief, essential facts of her day, in the precise order of their occurrence and without favor. She had a knack for holding the extraordinary in equal measure to the everyday—news of my brother’s birth paired comfortably with a grocery trip to the A&P.

Today’s gathering puts me in mind of one such entry. I do not think she would mind if I read it to you.

“March 31, 1988: 88 (degrees). Had a tint and a hairdo, also had eye brows plucked. Great news from Helen! Ann Marie called—she won a pulitzer prize. We’re very happy for her.”

I do not know what any of you were doing when word of your Pulitzer reached you, but I’m guessing that the news turned an ordinary day into an extraordinary one, and forever sealed your membership in what former Pulitzer Board chairman Skip Gates called the “aristocracy of excellence.” In Columbia’s annual printing of a soft cover compendium titled, simply, “The Pulitzer Prizes,” your names now join the ranks of other giants of journalism, letters, and music, American nobility including Robert Frost, August Wilson, Eudora Welty, Mike Royko, Samuel Barber, and Katherine Graham.

But these are not ranks into which you are born, nor does stature or wealth add a thumb to the Pulitzer scale. Were I to quibble with Skip, a privilege I enjoyed while we served on the board together, I would wonder whether “meritocracy of excellence” was more apt, recognition of the extraordinary industry and creativity which earned you a place at this ceremony.

Prize-giving is a fickle business, not determined by the precision of a stopwatch or scoreboard. The winners gathered here are the beneficiaries of the judgment of 19 arbiters, scrupulous and exacting judges to be sure, but human and guided by their own tastes and fancies. But that is not the same as arbitrary. There are qualities that endure, historic hallmarks of Pulitzer-worthy work that the board holds ever tightly even while expanding the eligibility rules. It was those qualities that distinguished the winners, whether traditional or multi-media, and that the board found abundant in your work.

Read the stories of government officials engorged on enormous pay packages or the medical mystery of a young boy racing against disease and renew your admiration for journalism that is probing and moral. Travel to Russia for a master class in foreign correspondence and criminal justice reporting and rediscover the meaning of dogged, both in print and online. Behold feature writing as forensics, an exacting reexamination of forgotten fatalities at sea animated by a playwright’s sense of timing. Meet anew the nation’s first president, and be reminded of how the familiar can be transporting in the hands of a biographer fortified by insight and scholarship. Stand in awe of a novelist’s meticulous braiding of lives across the wreckage of time and marvel at a skill that, in one chapter, renders even PowerPoint as literature.

In another moment President Bollinger will award you the tangible evidence of your prize and with that I offer but two more thoughts. Not long after I hung the Pulitzer certificate as evidence of my fortune, I came home to find my husband had placed into the frame a competing commemorative notice—a form letter from the Illinois Secretary of State’s office congratulating me on my safe driving record. If you are lucky, as I was, there are people in your life to keep you humble. Those are likely people who made some sacrifice in support of your work, and to those spouses, children, friends and colleagues, we offer our very deep gratitude.

Lastly, the late Howard Simons, former Nieman curator and managing editor of the Washington Post, used to warn Pulitzer winners against playing out their careers trying to repeat their grand slam with every at bat (advice, by the way, clearly ignored by photographer Carol Guzy of the Post, who today is awarded her fourth Pulitzer, a record for a journalist). While it was the clear intent of Joseph Pulitzer that the prize be a beacon offering both model and reward, it is also true that lots of great work goes unrewarded. An author I know recently admired a book as the one that he most wished he had written. It’s one of my favorites too and was a finalist for a Pulitzer but did not win, a fact that has never tarnished the book’s luster.

It did achieve the only thing that is in the creator’s control, what Amanda Bennett, the recent past co-chair of the board, holds as the standard for her reporters: producing journalism that may or may not win Pulitzers, but is worthy of Pulitzers.

Who can write again the script that got them here? It would be lovely to see you back in the Lowe Library some spring, but joyous still to read more of the kind of work that got you here today. For that is hard enough and the true legacy of Pulitzer.

Kay Ryan, our poetry winner, wrote a poem called “The Job.” It says:

Imagine that

the job were

so delicate

that you could

seldom—almost

never—remember

it. Impossible

work, really.

Like placing

pebbles exactly

where they were

already. The

steadiness it

takes . . . and

to what end?

It’s so easy

to forget again.

On behalf of the members of the Pulitzer Board, and with great personal admiration, I congratulate you all on work so very well done.

Thank you.