2012 Pulitzer Prize Luncheon

Remarks by Gregory Moore

Co-Chair, The Pulitzer Prize Board, 2012-2013

I am Gregory Moore, editor of The Denver Post and co-chair of the Pulitzer Prize Board. On behalf of the Board, and everyone associated with our work here, I want to welcome you to this special occasion. It really doesn't get better than this.

The smiles are bright and broad, the wine is flowing, the chests are poked out and new bonds are born. And that is just on a personal note.

But it is fitting that these awards and this luncheon come this time of year. This is the season of renewal and so it is for our craft. It is an honor and privilege to read the great work being done in our industry and I know everyone engaged with the work comes away inspired -- from jurors to the Board itself.

It is simply breathtaking to see the work that makes it into print and onto our various websites. Whatever, one might want to say about the challenges facing journalism today, the newsrooms are not the problem.

So your presence here proves it once again, that fabulous work can be done anywhere, by anyone. What makes this day even more special is you can share it with loved ones, spouses and significant others who make a lot of sacrifices so we can do what we do.

To our winners, this is a day you'll never forget. Drink it all in, enjoy it and savor it.

The only thing that might be better than today is a tomorrow in which you find yourself sitting here again. And that will mean you will done something really amazing for journalism, for your communities and for yourself.

Again, welcome and congratulations.

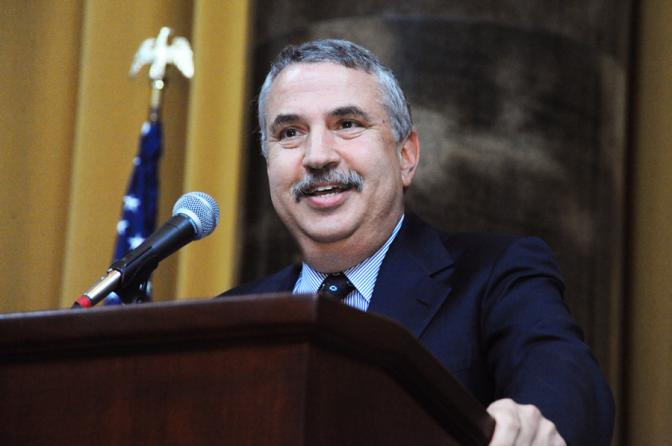

Remarks by Thomas Friedman

Co-Chair, The Pulitzer Prize Board, 2012-2013

On behalf of Greg Moore and myself, I want to thank you all for being here this afternoon at this happy occasion. Before I share a few remarks, I want to say that I am entering my ninth and final year on this Board and throughout that time I and my colleagues have benefited from the endless good judgment, good cheer and even temper of the Pulitzer Administrator, Sig Gissler. The Pulitzer Trust and Board are hugely in his debt. Anyone who has served on this Board during Sig’s tenure will tell you that.

Since the only thing standing between you all and your Pulitzer Prizes is my speech, I promise I will not be long. I thought I would simply take a few minutes to share with you what I have learned from eight years judging the best journalism produced in this country.

For starters, the first thing I have learned is how much good journalism still gets produced in this country, despite the shrinkage of news holes and news budgets. While we on the Board only get to see the best of the best – the three finalists in every category chosen by the different juries – more often than not I find myself wanting to give prizes to all three. It is often excruciatingly hard to choose. Our industry may not be so alive and well, but our craft certainly is.

As a Board member one not only gets to savor all this good journalism but to learn from its substance as well. In that regard, I have noticed a worrying trend. In recent years, but particularly this year, the finals included numerous stories about state and local governments, as well as the Federal government, being squeezed by budget cuts, and, as a result, either failing to do their jobs, or outsourcing them to private contractors, who, motivated more by profit than civic duty, often under-performed as well.

Here is a sample of what I mean from a few of our finalists and winners this year.

The Miami Herald offered a "sweeping, thorough, and meticulous investigation, over a year-long period, that uncovered abuses and lack of state oversight at Florida's once-acclaimed assisted living facilities. The Herald conducted hundreds of interviews and examined thousands of state inspections, police reports, and court cases. Through careful reconstruction of individual cases, it showed how some of Florida's most vulnerable citizens suffered grievous injury or death because of neglect and abuse, and how the state failed to shut down homes even after repeated violations."

The New York Times, through exhaustive reporting, "revealed rapes, beatings and more than 1,200 unexplained deaths in state-run facilities that aid 135,000 developmentally disabled citizens… They also found that New York taxpayers were paying far more for care than citizens in any other state, with some organizations handing top executives handsome salaries and questionable benefits."

The Chicago Tribune, using "old-fashioned investigative techniques… presented a clear and convincing indictment of a system that allowed criminals by the dozens to escape the consequences of their brutal acts by fleeing the country. Reporters did what law enforcement failed to do: they tracked down these violent fugitives, often living under their real names and interviewed many of them, along with families victimized by their crimes. The reporters also identified the law enforcement agencies, which through neglect or indifference, apparently forgot that crime without punishment is justice denied."

The Seattle Times whose "Methadone and the Politics of Pain" provided a compelling report on "how a little known government agency moved Medicaid patients from safer pain control medication to the more dangerous, but cheaper, methadone."

The Maine Advertiser-Democrat,which "exhibited extraordinary resourcefulness and tenacity in exposing a stunning failure by local, state and federal housing authorities to protect the most vulnerable members of their small, rural Maine community. With only a staff of three, the paper’s robust reporting and photography uncovered a blatant disregard for health and safety codes that prompted the state to launch an official investigation literally within four hours of publication of the first story."

The Associated Press on nuclear power plants for "clearly and dispassionately exposing how regulators have walked away from traditional standards of safety, even as nuclear facilities reaching or surpassing their life expectancy show troubling signs of leakage, decay and outright failure."

And, finally, California Watch and the Center for Investigative Reporting offered a "shocking discovery of deficiencies in the seismic safety of California's school buildings."

It is a truism that Americans of all political stripes want more government than they are willing to pay for, but I must say the effects are starting to show. We are leaving a period of 50 years when to be a president, a governor, a mayor or a college president, was, on balance, to give things away to people and we are entering a period – hopefully brief – in which to be a president, a governor, a mayor or a college president will be, on balance, to take things away from people. How intelligently we do that is going to determine a lot about the quality of life in our country. You can grow without a plan, but you better not cut without a plan. I suspect that a lot of what our news organizations will be covering in the next decade is how we cut things -- how intelligently we use our shrinking resources and what impact or failure to do so has on businesses, schools, jobs, families and the social fabric. In other words, we have a hugely important task waiting for us down the road.

Another thing I have noticed these past eight years is that the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post sure win a lot of Pulitzer Prizes for international reporting, and I am going to make a prediction: They are going to win a lot more, alas, because so many other news organizations have cut back on their foreign coverage.

I was in Amman, Jordan, two weeks ago and gave a talk at the Teachers College in Amman, where Columbia University also has an outpost. At the reception afterwards, a man came up to me, warmly shook my hand and asked, "Do recognize who I am?" I did not. He was Yousef Nazzal, the owner of the Commodore Hotel, the famous press hangout for the Beirut press corps for many years, culminating with the Israeli invasion of 1982. I was thinking about the Commodore in preparing these remarks. When I looked around the Commodore lobby there in the summer of 1982, I saw correspondents from the Washington Post and New York Times, as well as from the Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Baltimore Sun, Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia Enquirer, Miami Herald, Dallas Morning News, Associated Press, Newsday, United Press International, Reuters, AFP, CNN, NBC, CBS, ABC, Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report. Every major British, French, Italian and Spanish paper was also there, along with photographers from every agency. Some of those news organizations don’t exist anymore, and some have so long ago given up foreign reporting they don’t even remember they were in it.

The upside, of course, is that a huge number of websites and bloggers have emerged to tell their stories, and many of them are locals who are telling their own story to the world – bravely, intimately and with the perceptiveness that only an insider can offer. I, for one, have benefited enormously from these new voices, like Now Lebanon, for instance. But I don’t know how many Americans have the patience or energy to ferret them out. And so I cannot help but feel a certain melancholy and unease that at a time when the world has never been more interconnected, and therefore interdependent, American news organizations have fewer and fewer resources to cover the globe. We are going to have to find more creative and cost-efficient ways to visit the world on behalf of our readers – before the world visits us again, as it did on 9/11.

Finally, people often ask, and especially this year when the Board did not award a prize for fiction, what our debates and discussions are like. Without speaking about specific entries, let me try to lift the shroud just a bit. Being on this Board is like being in the best book club in the world. And yes, the debates do at times get heated. I will always savor the opportunity I had to watch Professors Henry Louis Gates of Harvard and David Kennedy of Stanford debating the merits of a particular book of history. Their back and forth was pay-per-view quality. At times it made you want to lean back, pop popcorn and just enjoy the show. I am always amazed in our discussions that one can be totally allied with one person on the merits of a particular book or piece of journalism and then their staunchest opponent on the next one. And I am equally amazed at how I can come in feeling one thing about a book or a series and be persuaded by another Board member’s original argument and insights about that work to vote the other way. It’s a strange mix: You have to walk in with both strong convictions and an open mind, because there are a lot of people smarter than you on any given subject.

Who wouldn’t pay attention to someone like Junot Diaz, a Pulitzer winner in fiction and now on our Board, incisively analyzing a novel, as only another fiction author can do, while he paces around our Board table, or lies flat on his aching back on the floor? It is like a great fiction class. Who cannot but be touched when our always soft-spoken fellow Board member Joyce Dehli reads aloud stanzas from her favorite poet to sway the Board to her side, before Danielle Allen, our Board member from the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study, deconstructs the same poem with her expert precision? I still miss Washington Post Publisher Don Graham’s passionate and baroque way of introducing any entry he liked or wanted to demolish. It was like watching a great lawyer opening a case. And I shall certainly miss the two women from the class before me who always sat next to each other – Kathleen Carroll, executive editor of the Associated Press, and Ann Marie Lipinski, curator of the Nieman Foundation. You only need to be on the Board with the two them for one year, let alone eight, to say to yourself: "How could there have been a time when women were not top editors?"

Through it all, though, I can tell you that I have never witnessed an iota favoritism or bias toward any paper or author. People truly take their judging duties seriously – to be executed, if I may use a motto close to home, without fear or favor. Yes, at times, as happened this year with fiction, there is no winner. But do not assume that was because nothing was found worthy. We usually have 15 people voting. Entries often win by small margins, but sometimes seven people can feel very strongly about an entry and the eighth vote just is not there. Don’t take that as a sign of our failing or anyone else’s. Take it as a sign of how strongly people feel about what they are voting on and their commitment to be true to their judgments and our standards – without fear or favor. So for all these reasons and more I want to say what privilege it has been to serve on this Board. It’s a lot of work, but I wish I could have nine years more. Well, maybe three…